A review by John Cook.

I am very much of the generation to which Luke Turner refers. I started off with my brother’s battered book of Biggles WWI adventures (Sopwith Camels anyone?)and I did eventually graduate to the WWII material and devoured the popular paperbacks of the post-war years that idolised tales of adventure under fire and the great escapes of the war ( from Bader to Colditz). It was not until many years later that I became aware of other sides of those conflict years. There were veiled references to the men involved in the concert parties that were common to the British and Australian Armies (remember ‘It ain’t half hot, Mum’?).As far as WWII, one of my key media memories has to be the TV American treatment of the theatres of war series such as ‘Victory in the Pacific’ with its effective theme music by Richard Rogers.

As my knowledge and understanding of the GLBTQI world of wartime grew, I became aware of how some relationships formed even under the most extreme circumstances (perhaps even because of it).I must confess the material was often limited in form and often included details of investigations to locate and punish such behaviour. It was also clear, however, that many commanding officers were content to ‘turn a blind eye’ so long as efficiency and morale had not been affected.( Vidal and serving in Silence?: Australian LGBT servicemen and women’ by Noah Riseman, Shirleene Robinson, Graham Willett 2018). My reading of Donald Friend’s memories of his service in Australia and New Guinea were especially enlightening. All of this was all male oriented and it took time for me to become more aware of female involvement though this became more apparent during the witch-hunt years of ‘rooting out’ homosexual behaviour that infected the British, American and Australian military scenes at all levels in the post war years. My main awareness grew from personal contact in my later years with Lesbians who had served.

I took up this book anticipating that there would be coverage of war-time activity but was a little surprised that the author had managed to nest these happenings within his own ‘growing-up’ experiences of modelling what had become famous WWII air force personnel. Luke went further than just this reading to the bomber and spitfire model-building stage and then trying to track down physically where many of the men and their planes were based. His descriptions of his visits to these often now ruined locations were very touching especially when supplemented by the words of so many aircrew before they set off on yet another sortie knowing full well what the odds on their non-return were (55,573 crew out of a total 125,000) as well as the full range of conscientious objectors. The overwhelming majority were straight men though gays were inevitably represented along with those who were still wrestling with their sexual identity. Some I knew of but was particularly taken by the inclusion of the father of one of my all-time English creatives, Derek Jarman. Luke points to..

“more like them, that I have spent the last few years getting to know as I researched this book. Men like Peter de Rome, who, after the war, made gay erotic films on Super8; Micky Burn, the commando who appeared in a documentary about his life as a bisexual man; Colin Spencer, a teenager during the war who, afterwards, would spend his National Service in Germany treating soldiers with VD; Dudley Cave, a gay activist I learned about via a tweet from Peter Tatchell; Dan Billany, who wrote two astonishing novels, one a gay love story set in an Italian POW camp; and Wing Commander Ian Gleed, a pilot whose Mk 1 Hurricane sat in my stash of unbuilt model kits and whose surprising private life was revealed when I searched for information about them”

So there is the potential link as Luke uses this background to look at his own emerging sexuality and how it was affected by these background experiences. I had to agree as a war baby myself who grew up in a world surrounded by those war experiences and seen through the eyes of my father, uncles and their friends. These influences were present in my schooling (Bren guns at cadets), listening to the attitudes of my father and his friends and even in the process of job-hunting. He compares our experiences with the youth of today..

“It didn’t matter that I didn’t have the latest trainers, wasn’t into the music that everyone else liked, was terrible at sport and physically underdeveloped, because I had this history to disappear into. I imagine it’s even harder to be an awkward young man now in the age of ubiquitous pornography, the toned bodies of reality TV, peer pressure of social media, impossible ideals of physical strength and physique. Who needs any of that if you can imagine yourself sitting inside a tank, spitting fire at the world around you?”

I was particularly taken by his remark. “post-war struggles with mental health and PTSD impacted the generations on” I immediately thought of an uncle of mine ( a Rat of Tobruk) who may well have fitted this description and whose early death and that of his son from identical causes. “Britain’s victory had a high psychological price many would argue we’re still paying”.

After numbers of hints beforehand, the author finally settles on a section devoted to looking at the experiences of men who were bisexual, unwaware or not. Certainly, the author comes to that conclusion about himself relating to the Freudian continuum . Once again, he does so by referencing letters, notes and poems of those who survived and those who didn’t.

There, he encountered the usual transvestism and sexual fluidity that so many men wrote about in their memoirs. It was a joke in the camp to say that men would be ‘home before Christmas or homo before Easter’.”

“Whether it was to Dorothy in Loughton or a friend of Dorothy in Warwickshire, men wrote of the very same things.”

The latter portions of the book pursue the author’s personal interest entwined with his musings on the continuing nature of war and how we respond to it viz the Ukraine Vs Russia conflict.

“It is the knowledge that such things have always happened through our human history, that they are happening now, that they will happen again, for they are a part of who we are.”

“History isn’t just packaged away into neat boxes as it is at school, or in TV programmes or popular books. It is with us constantly, evolving and shaping our lives in every second of the present. Without the Second World War, without the most horrendous unimaginable and unrepeatable moments in it, I would never have known my son.”

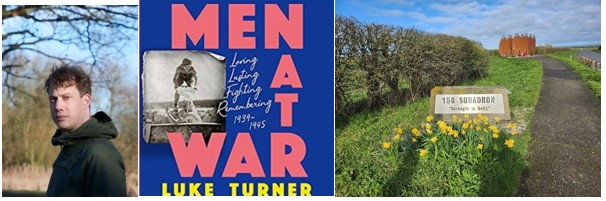

One key repeated element for the author is his fierce interest in 158 squadron based at Lissett and the fate of its squadron association and eventual creation of a memorial which I found profoundly effective and have included a picture of it in this report in the light of the cost of expanding the Australian War Memorial.

This is a profoundly thoughtful book and I recommend it to anyone wanting to plumb the depths of human sexual behaviour in war time that includes a range of sexualities.